The time I met my girlfriend’s ex-boyfriend was on their very first date: June 2, 2018. I know because I have iPhone photos. It was my ex-boyfriend’s 25th birthday and I was throwing a backyard party. The humidity was high. The unofficial theme was corrupted youth, evident by the macabre watercolor drawings taped to the brick walls and my twenty-four-year-old body busting through a child’s teddybear pajama top. For hours we sat in lazy circles on muddy grass drinking Modelos and passing an overweight chihuahua around like a joint. Emilie arrived as the sun was cooling and the quarter tab of acid I’d taken was wearing off. I hugged her hard, stepping right onto her brand-new white sneakers. (They were Prada, she reminds me now. I tell her: She shouldn’t have bought white Prada sneakers in the first place.) She introduced me to—let’s call him Eric—but I have no memory of speaking to him at all. I can’t tell you what I said or what he looked like; only that for the rest of the party, they were off to the side, leaning deeper and deeper into conversation. I drifted back in and out of banter, gifted my ex his first e-cigarette, and didn’t see Emilie again for another four years.

In that time, I would dump my dude and move to California. The Great Pandemic of 2020 would rock the planet, and Emilie would move to New Mexico, where Eric’s family was from. Like many, the pandemic allowed Emilie and Eric to live out their homemaker’s dream. They resided on a pecan orchard in Las Cruces where they baked bread, and watered trees and took photos of things that resembled snakes. They’d drive to White Sands and fight for the aux cord and taste every green chili stew in the state. Because down in New Mexico, Hatch chilies are the Champagne of peppers and everyone has a recipe for green chili stew.

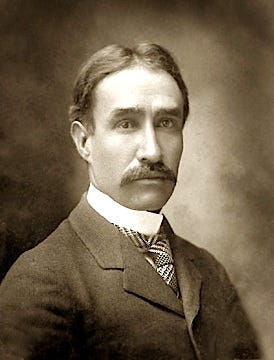

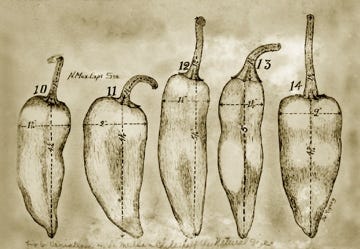

The history of the Hatch chile is full of proprietary myths and contradictory claims, with each grower offering his own version of its origins. Though some pepper peddlers may argue otherwise, New Mexico State University’s Chile Pepper Institute asserts that there is in fact no variety of chile pepper actually named Hatch. Rather, Hatch refers to the town in New Mexico where the many varieties of New Mexican pods are grown, including: NuMex-Big Jim, -Joe E. Parker, -Conquistador, Española Improved, Sandía, Anaheim, and New Mexico 6-4, all of which owe their existence to a visionary Mexican-American horticulturist named Fabián García (1871-1948). Garcia knew that by breeding milder New Mexican Chilies, the pods could be consumed in greater quantities and farmers could therefore, sell more of them.

He is also responsible for planting the first pecan trees in New Mexico! Now, New Mexico is home to 30,000 acres of pecan trees and a booming chile industry that brings in more than $300 million each year, with the chile pepper firmly rooted as a symbol of the state’s culture, pride, and identity.

In May of 2024, Emilie and I moved in to a small brown house on Euclid Ave—far from the nicest on the block. With its thirsty front lawn and droopy gutter, it’s taken a lot to give this outdated rental some curb appeal. Potted herbs, a porch swing, a SpongeBob-themed welcome mat that no one but I seem to appreciate. But my wood-stained and weatherproof accessories ain’t doing much to keep us up with the Kardashians. This sleepy little suburb of Pasadena is a bike-friendly trove of Basset Hounds, Victorian turrets, and well-to-do families, young and old. Without children, or dogs, or a landscaped footpath, it’s easy to feel like an outsider. Like we’re two odd birds in a tight-knit flock.

Then in September, a flyer appeared in our mailbox inviting us to participate in the Madison Heights 3rd Annual Chili Cookoff (Text Andrew to enter).

There was no question of whether to make chili, only a question of what chili to make. Unlike traditional potlucks, where diversity is encouraged, chili contests demand uniformity: everyone makes their version of the same dish. Cooks must assert their individuality within the bounds of conformity—not by breaking the rules, but by stretching them just far enough to stand out while preserving the essence of what chili is.

As we contemplated how to distinguish ourselves, Emilie asked me: Have you ever had New Mexican green chile stew? And I said: Yes, in fact, I have.

I went to New Mexico once. Santa Fe to be specific. Winter break, my senior year of college. I dragged with me the guy I had been dating for all of two weeks and forced him to get on a snowboard. When we were sufficiently sore and potentially concussed, we unclipped our helmets, unstrapped our boards and hobbled over to Totemoff’s, the mid-mountain rest-stop where I expected to make do with the average ski lodge fare: re-heated chicken tenders, greasy pizza slices and hot-cocoa water. Clearly, I had forgotten where I was. This was New Mexico! Every place you go is boasting their own homemade green chile special: green chile milkshakes, green chile sushi, green chile burgers, green chile brats, green chile Frito-pie, and of course, a green chile stew.

When the unassuming, white cardboard cup of piping hot stew arrived, the steam billowed up, carrying hints of roasted chiles, garlic, and cumin. The first spoonful hit me like a revelation. The pork so tender it melted in my mouth. The broth, ever-so slightly thickened by pieces of potato. And the green chiles, bright yet assertive—pushing a heat that burns slow, and warms you from the inside out. It was pure joy. By far, the greatest ski lodge food I had ever had and perhaps the greatest stew as well. No slapdash burger or soggy nachos, but something distinctly regional, complex, and satisfying. I looked at my date beside me, his cheeks red from the wind. Isn’t this incredible? I asked. It’s too spicy, he said with a baby-like giggle. And in that moment, I knew I'd be chasing the heat of that green chile stew long after I had left both him and the mountain behind.

So when Emilie suggested we enter the chili cookoff with our own version of a New Mexican Green Chile stew, I was game. Not only because I thought it would make a strong contender, but because I hadn’t tasted that hot, savory, green stew since the ski trip seven years ago. And I wasn’t the only one carrying something with me from a relationship past. Emilie had Eric’s mom green chile stew recipe and the memory of a hundred other green chile stews she had eaten during the course of her Southwestern romance. Now it was our time to shine. To answer the call. To make like Dr. Fabián García, and innovate.

Eric’s mom’s recipe was just a start, and Emilie had lots of ideas for how to make it better. She wanted to introduce ingredients and techniques from her Chinese-Cuban background. She had ideas for what cut of meat she wanted to buy, and how small to dice the potatoes. She wanted to spread refried beans on the bottom of each serving bowl and roll up a hot tortilla to go with it. It sounded like the best pork green chile stew I’d ever have, but I was worried: Was it chili enough for the cookoff? What if the judges are sticklers? What if they say there aren’t enough beans? And where are going to find New Mexican green chile in Los Angeles anyway?

Week after week we returned to the Hollywood Farmers’ Market and checked grocery stores for any sign of Hatch peppers. Then one weekend, we struck gold, or shall I say, struck green. One of the purveyor’s was peddling a bounty of New Mexican green chile peppers, but grown in California. Without the Hatch soil, altitude, and climate, would these “New Mexican” pods have the same distinct profile we were looking for? There was only one way to find out.

We purchased ten pounds and roasted half of them. We made a test stew and served it to all of our friends. The feedback was just as I feared: it’s delicious, but not quite chili. I convinced Emilie that if we stood a chance at winning this thing we needed less potatoes, and more beans—whole beans, not refried. And some shredded cheese on top. Even though I loved (and preferred) her original version, I felt we needed to conform. To make sure that people still identified what we were making as “chili.” She acquiesced.

The day before the cookoff, Emilie worked like a chef possessed. She roasted, peeled, and chopped the chilies. She trimmed, diced, and marinated the pork shoulder. She chopped onions and soaked beans. By 11 p.m., we were finally ready to try the stew.

“Spicy,” I said, my voice echoing the guy I’d once strong-armed into snowboarding.“Too spicy?”

Emilie nodded, her expression pensive. It was really spicy. Maybe that was the price of growing Hatch chilies outside Hatch. Thinking of the children and adults with childlike palates, I started bracing for defeat. Losing won’t be so bad, I convinced myself. We could go home with a nice shiny Loser’s Ribbon and spin a charming tale about our underdog effort.

We left the pot simmering overnight, and with luck, the next morning, the flavors had softened and deepened. By three o’clock, like it or not, it was time to roll our chili out into the arena. We dragged our camp chef and propane, our ladles and stock pots down the block to where the event was taking place.

We set up under a shady tree and met “Andrew” from the flyer, who had moved here from Tennessee and taken his annual chili contest tradition with him.

Nineteen other contenders lined the street, each pushing the boundaries of what chili could be: sweet Filipino chili, vegetarian Argentinian chili, an Indian curry chili, a classic Texas chili, a seven-pepper chili, even a pineapple chili. Somehow, word of the contest had hit the local paper, drawing over a hundred people from all corners of town.

The competition was fierce, but Emilie and I were in our element. She filled bowls and warmed tortillas, I rolled them up and garnished with cheese. We were a chili-slinging machine. Yet doubt lingered—was our chili good enough to stand out among the rest?

Slowly, more and more people trickled to our table. They dropped votes in our bucket, complimented us, asked for seconds, and even thirds. Soon, the floodgates opened. Strangers swarmed us, saying our chili was the talk of the event. Some claimed they’d been told not to leave without tasting it. By five o’clock, we were scraping the last of the second pot.

Andrew climbed onto a very official step-stool to announce the winners.

“In the Popularity contest, the winner is… Team Tomato Play!”

Applause erupted.

“And in the Critic’s Choice category, the winner is… Team Tomato Play!!!”

Reader, we couldn’t stop laughing. To win both categories—to sweep the competition—felt surreal. The new kids on the block, crowned Chili Champions. Emilie beamed as Andrew handed us two trophies, their grinning faces as ridiculous as ours. I climbed the step-stool for my improvised acceptance speech, thanking our neighbors for welcoming us, our friends for supporting us, and Emilie’s ex-boyfriend for inspiring us.

A few days after our big win, I read Emilie the draft of this underdog story, offering it up like she does when she serves me a spoonful of chili—testing to see if it needs anything. She listens, her focus razor-sharp. When I finish, she says it’s good. But I can tell she thinks something is missing. What?

Do you really want to know why I wanted to make the green chile stew? she asks, her tone already guilty. My chest tightens in anticipation, like I already know what she’s going to say.

Sometimes recipes have secret ingredients, and sometimes they just have

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tomato Play to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.